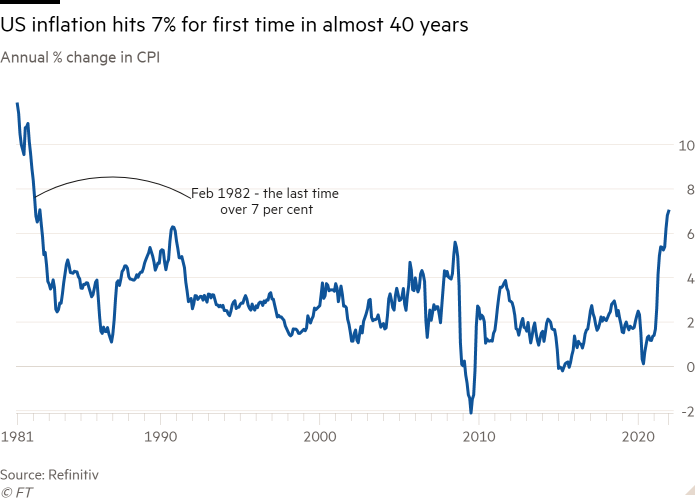

US consumer price growth rose at the fastest pace in almost four decades in December, stoking the Federal Reserve’s fears about the threat of elevated inflation and its consequences for the economic recovery.

The consumer price index (CPI) increased at a 7 per cent year-on-year pace last month, a step up from the 6.8 per cent rate registered in November and the largest jump since June 1982.

Despite the faster annual pace, month-over-month price gains moderated to 0.5 per cent between November and December, down from 0.8 per cent in the previous period.

“Core” inflation, which strips out volatile items such as food and energy, accelerated by an even larger magnitude compared with the last reading.

It rose 5.5 per cent, well above the earlier 4.9 per cent annual pace. That translated to another monthly increase of 0.6 per cent, the sixth time in the last nine months that figure has exceeded 0.5 per cent, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“There is nothing in the details of the data that suggest inflation is fading in any meaningful way,” said Eric Winograd, senior economist for fixed income at AllianceBernstein.

A rise in shelter costs and prices for used vehicles were the “largest contributors” to December’s increase, according to the BLS. Shelter costs, which have climbed steadily in recent months, reached a 0.4 per cent pace in December. Since December 2020, those expenses have increased 4.1 per cent. Used car prices continued to zoom higher, increasing 3.5 per cent from the previous month, and almost 40 per cent from a year ago.

Energy prices fell 0.4 per cent from November, the first decline in months, and gasoline prices dipped as well.

Food prices also contributed once again to the historically high figures. Dining-out costs rose 0.6 per cent from a month ago, a 6 per cent year-on-year increase, the largest rise since January 1982.

The broader food index was up 0.5 per cent, a more modest pace than the previous period. Costs of apparel costs, household furnishings and medical care also rose.

The data, which were released by the BLS on Wednesday, come just a day after Jay Powell, chair of the US Federal Reserve, warned high inflation was a “severe threat” to the labour market recovery and affirmed the central bank’s intentions to rapidly reduce its monetary policy support.

“The Fed is now behind, so the urgency you hear in Powell’s voice on inflation is him playing catch-up,” said Tom Porcelli, chief US economist at RBC Capital Markets. “The justification for the Fed to respond to inflation happened months ago.”

He expects the Fed to raise rates four times in 2022, beginning in March, and another four times in 2023.

Senior officials have begun to sketch out their plans to raise interest rates from their near-zero levels once they reach their dual goals of maximum employment and inflation that averages 2 per cent over time.

December’s data showed further signs that inflation is picking up in a broader cross-section of the economy and is at greater risk of becoming entrenched. It will also pile further pressure on the Biden administration over its management of the economy heading into the 2022 midterm elections.

While the US president has presided over a booming economy that created more than 6m jobs last year while the unemployment rate fell to 3.9 per cent, the perception of a strong recovery has been undermined by the spike in prices and supply chain disruptions.

“This is obviously an area of real challenge . . . Americans feel the price squeeze,” a senior White House official told the Financial Times. “While projections expect moderation [of inflation] across the year, the president and the administration are focused and trying to pull that forward as much as possible.”

The White House has been trying to reduce bottlenecks at key ports, crack down on anti-competitive behaviour in certain markets such as the meat industry and encourage more oil production globally to reduce petrol prices. It has refrained from adopting other inflation-fighting measures, however, such as removing tariffs on Chinese imports.

US inflation data prompted an abrupt pivot from the Fed late last year and has swayed global financial markets for months. But Wednesday’s reading, which was largely in line with economists’ forecasts, did not immediately ripple into the $22tn US Treasury market.

The yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury fell 0.01 percentage points to 1.72 per cent following the data, with marginal selling pressure pushing the yield on the policy sensitive two-year note up 0.01 percentage points to 0.89 per cent.

The US stock market opened higher, as investors digested data that appeared to keep the Fed on track for four quarter-point rate increases this year.

“The Fed is facing both a labour market that is acting like it’s closer to maximum employment and inflation that is elevated,” said Tiffany Wilding, an economist at Pimco. “It suggests that their policy should be closer to neutral as opposed to being extraordinarily easy.”

“Their policy pivot is consistent with that,” she added.

Additional reporting by Eric Platt and Kate Duguid in New York

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMiP2h0dHBzOi8vd3d3LmZ0LmNvbS9jb250ZW50L2I5MGY1OWUxLTc5YzItNDAzZC05NGE5LTc3NjU1NWM1NDFmY9IBAA?oc=5

2022-01-12 13:35:44Z

1246375635

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar