Developing economies’ limited access to Covid vaccines threatens to hinder the global economic recovery from the pandemic, the IMF has warned, as it upgraded its growth projections for advanced economies but lowered them for other parts of the world.

The Fund still expects overall global growth of 6 per cent this year — unchanged from its last projection in April — it said in its latest World Economic Outlook on Tuesday. But it warned that new waves of coronavirus infections since then, including the spread of the Delta variant, have made the outlook more uncertain and uneven.

“Vaccine access has emerged as the principal faultline along which the global recovery splits into two blocs,” the IMF said. Some countries “can look forward to further normalisation of activity later this year” but many others “still face resurgent infections and rising Covid death tolls”.

Even countries on the recovery track should not be complacent about this, the Fund warned: “The recovery . . . is not assured even in countries where infections are currently very low so long as the virus circulates elsewhere.”

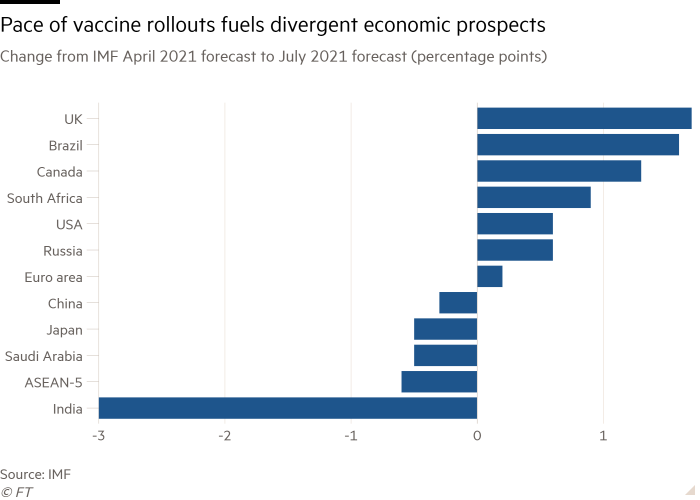

The IMF cut 0.4 percentage points off its growth forecast for emerging and developing economies this year, to 6.3 per cent. The gloomier outlook was worst in south-east Asia and south Asia, particularly India.

By contrast, the IMF increased its forecast for advanced economies’ output growth this year by 0.5 percentage points to 5.6 per cent, with notable upgrades for the US, UK, Canada and Italy. France and Germany were unchanged, while growth expectations for Spain and Japan were downgraded.

IMF chief economist Gita Gopinath told the Financial Times: “We’re still in a situation where the pandemic is creating a lot of havoc around the world.”

Although it was clear the Delta variant was “quickly becoming the dominant strain”, the economic impact in wealthier nations was hard to judge, she argued.

“While we are seeing cases go up . . . if you look at hospitalisations and deaths, you’ve seen a far more muted effect . . . We have to see whether this will actually have a big hit on spending patterns, on travel, on confidence effects and so on. And we aren’t seeing that yet,” she said.

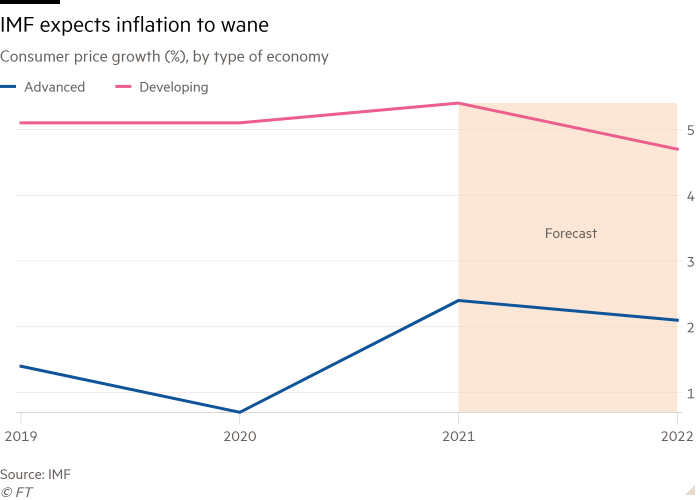

One significant risk the IMF identified was inflationary pressures. Although the world’s major central banks expect the pace of price growth to peak later this year and then ebb, the Fund warned that inflation could turn out to be more persistent than it had anticipated.

There is a risk that this could prompt a more aggressive normalisation of central bank policy, which would hit emerging and developing economies particularly hard, it said.

“A double hit to emerging market and developing economies from worsening pandemic dynamics and tighter external financial conditions would severely set back their recovery and drag global growth below this outlook’s baseline [scenario],” the IMF said.

However Gopinath said she was “not worried” about the risk of an inflationary spiral in the US, where the Biden administration’s spending plans are expected to fuel the economic recovery.

The IMF upgraded its growth forecasts for the world’s largest economy by 0.6 percentage points this year and 1.4 percentage points next year, to 7 per cent and 4.9 per cent respectively — on the assumption that Washington’s infrastructure and social spending programmes will pass through Congress.

US Federal Reserve policymakers will meet on Wednesday to discuss a possible reduction in the pace of its asset purchases later in the year, as it starts to slow the pace of monetary support for the recovery.

The Fed’s favourite inflation gauge — the core personal consumption expenditures index — is expected to accelerate sharply from its current 3.4 per cent level to eventually reach 4 per cent. But as transitory supply constraints and other pandemic-related quirks ease, those pressures will fade, with core PCE drifting down to 2.5 per cent next year, the IMF forecasts.

“Everything we’ve seen so far is in line with the prediction that inflation comes down next year,” Gopinath said.

The Fund’s projections for inflation and employment suggest that US interest rates will start to rise in late 2022 or early 2023, Gopinath said — more quickly than Fed officials have predicted.

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMiP2h0dHBzOi8vd3d3LmZ0LmNvbS9jb250ZW50LzI4ZjhjMTNkLTJkYzMtNDEwNi1hNDhlLTRjNjI4ZjM5MmEwOdIBP2h0dHBzOi8vYW1wLmZ0LmNvbS9jb250ZW50LzI4ZjhjMTNkLTJkYzMtNDEwNi1hNDhlLTRjNjI4ZjM5MmEwOQ?oc=5

2021-07-27 13:02:50Z

52781754890977

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar